3 lessons a designer can learn from a biotechnologist and an environmental chemist one week before lockdown

In November we were hosting in our Viennese lab a brilliant young designer and a sustainable colour researcher Julia Kaleta from Amsterdam. Here is the part 1 of her behind-the-scenes experience, captured in a personal blog.

Last month I visited Vienna and worked alongside women who are developing one of the most fascinating methods for textile dyeing. We planned this visit in September, when Karin Fleck (CEO and founder), Iva Hafner (business developer), and I met in the Fashion For Good museum. Do you recall this feeling when summer is over but the sun is still there, the feeling of excitement and thrill of new beginnings that the autumn season is going to bring? For me this atmosphere is rooted in memories of the start of the new school year, when you are recharged after the summer break, ready to jump into new projects. That atmosphere was there, in our meeting, when we met for the first time in person after being in touch via e-mails since the first lockdown in 2019.

Fast forward 3 months and here we are – a national 4th lockdown in Austria meant that I came back to Amsterdam sooner than was planned. Fortunately, I arrived in Vienna exactly one week before the preventive measures came into place. I could introduce myself to my new colleagues without wearing face masks, which definitely helped create trust and a fun atmosphere. We could still see smiles on each other’s faces. But only for five days. The “lockdown” in the air made me feel like I was at a speed-dating event, which is why I decided to not waste a single moment and make the most of the stay, asking obscene amounts of questions.

Lesson 1: What needs to happen to create a colour with the help of microbes?

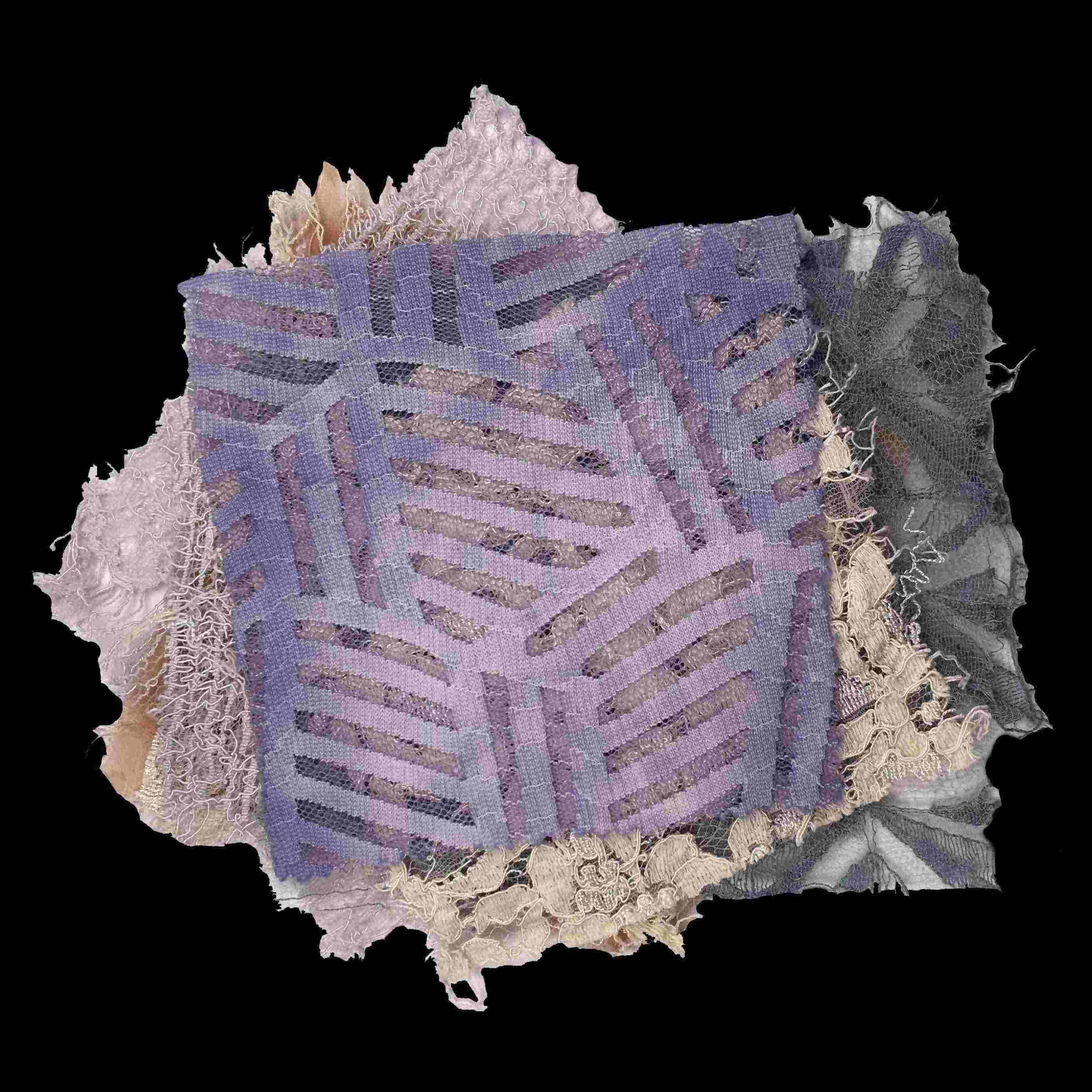

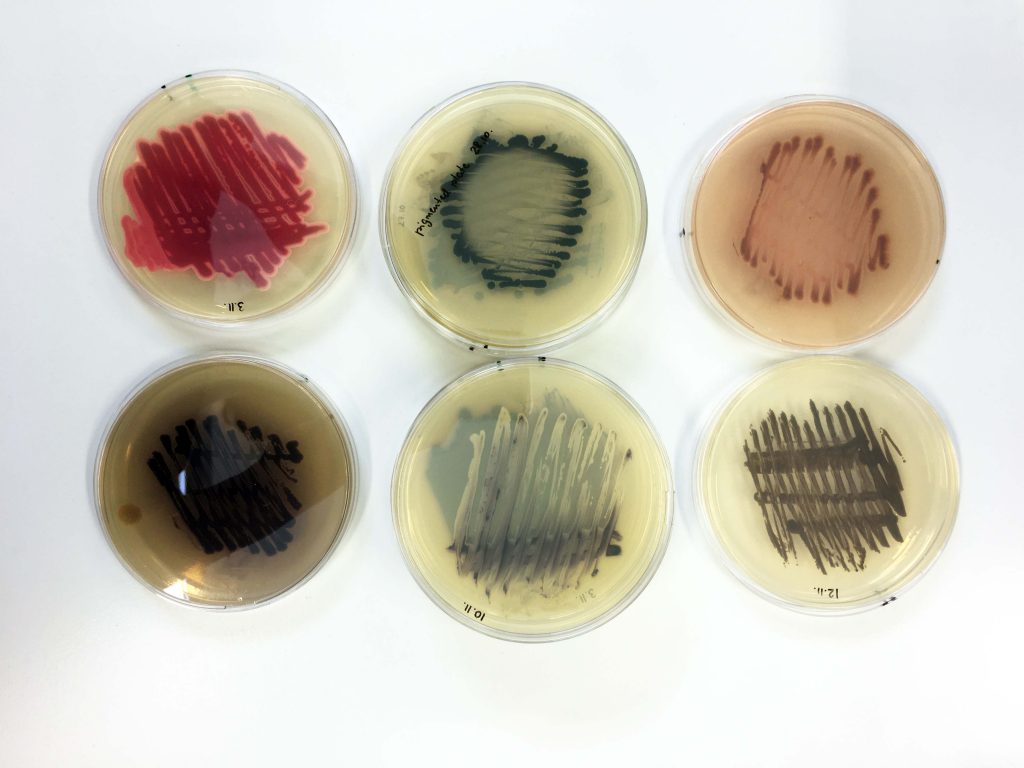

You need to know that working with bacteria and textiles requires time and patience. Nevertheless, a friendly atmosphere is just as important as a proper medium, the ‘food’ bacteria need to grow in flasks. I learned that from Mascha, a bioprocess engineer, who works with yeast, bacteria, and fungi. Amongst many other responsibilities, Mascha is cultivating bacteria in bioreactors where she can create a defined environment to grow them in bigger quantities. She taught me a lot about the technicalities of a microbial dyeing process. We discussed the importance of a sterile environment, as well as the fact that in nature colour is often produced as part of a defense or survival strategy. What are the triggers? ‘Predominantly a change in the environment that calls for protection e.g. against competitors or exposure to UV light’. Every day in the lab Mascha observes bacteria that produce pigment under just the most charming conditions, ‘..they are happy in the culture, provided with a perfect combination of nutrition and oxygen supply, and there is no competitor.’

These personal observations are important while working with microorganisms, picked straight from the environment. Working on the improvement of this technology and developing an understanding of what bacteria need in order to leave the most efficient amount of the pigment to dye fabric is a meticulous process, which requires time. You may ask, does the industry have the patience for that? I’d like to invite you to reflect on the time and patience we can learn from working with nature, in order to mimic it and restore balance in the environment we live in. Cliché? I see it more as the truth we need to keep repeating in order to slow down and appreciate the value of nature-based materials and solutions, rather than seeing them as the ‘hype’ and too-expensive-to-be-truth.

Lesson 2: Environmental impact and the future of functional colour

My second speed date was with Célia, an environmental chemist who is looking at all aspects of microbial colours that include testing environmental parameters. I asked Célia about what needs to happen in order to replace the synthetic dyeing with the bacterial one and indirectly support her work. The first thing she said was that the awareness in people about the consequences of textile dyeing needs to increase, and a will to change. Her second point was that politics plays a huge role in demanding from all of the players in the industry implementation of green practices. Célia added ‘there are regulations which need to be introduced in all of the countries which are producing and dyeing the majority of our textiles, but there is a problem that regulations which exist are not always respected. We need to take responsibility for the environmental and social impact of the textile industry. In Europe, there are more controlled restrictions regarding the release of industrial effluents in the environment. That means that if we do the dyeing here, we have more control on the industrial chain.’

The increased awareness of people – of all of us – was mentioned above twice. When we discuss the price of bacterial vs synthetic dyes we really need to stress the fact that the former is a natural source of pigment, abundant in nature, while the latter one is based on petrochemicals and uses more of the precious natural resources. The environmental cost of synthetic dyeing is perfectly depicted and explained in Andrew Morgan’s iconic documentary ‘The true cost’.

***

This blog will continue with part 2 soon, so stay tuned.

I would like to thank the team of Vienna Textile Lab for sharing their knowledge and co-editing the blog.